Alzheimer's disease

Highlights

Alzheimer’s Disease

Dementia is significant loss of cognitive functions such as memory, judgment, attention, and abstract thinking. Alzheimer’s, the most common form of dementia, is a progressive brain disease. It affects more than 5 million Americans, and millions more worldwide.

Risk Factors

Age is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Most people who develop Alzheimer’s disease are 65 years old or older, and the risk increases with age. People age 85 years and older are especially at risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Symptoms

Early symptoms of Alzheimer's disease may include:

- Forgetfulness

- Loss of concentration

- Language problems

- Confusion about time and place

- Impaired judgment

- Loss of insight

- Impaired movement and coordination

- Mood and behavior changes

- Apathy and depression

Treatment

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Drug therapy aims to slow disease progression and treat symptoms associated with the disease. The benefit from drugs used to treat Alzheimer’s disease is typically small, so that patients and their families may not notice any benefit.

Patients and their families need to discuss with their doctors whether drug therapy can help improve behavior or functional abilities. They also need to discuss whether or not drugs should be prescribed early in the course of the disease or delayed.

The following drugs are commonly prescribed for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease:

- Donepezil (Aricept)

- Rivastigmine (Exelon)

- Galantamine (Razadyne)

- Memantine (Namenda)

Introduction

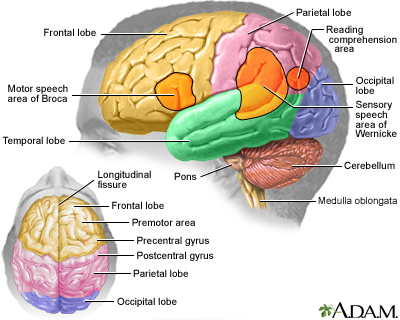

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive degenerative disease of the brain from which there is no recovery. The disease slowly attacks nerve cells in all parts of the cortex of the brain and some surrounding structures, thereby impairing a person's abilities to govern emotions, recognize errors and patterns, coordinate movement, and remember. The changes in the brain may begin to develop more than 20 years before symptoms develop. Ultimately, a person with AD loses memory and many other mental functions.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia in people age 65 years and older. Dementia is significant loss of cognitive functions such as memory, judgment, attention, and abstract thinking.

There are three brain abnormalities that are the hallmarks of the Alzheimer’s disease process:

- Plaques. A protein called beta-amyloid accumulates and forms sticky clumps of amyloid plaque between nerve cells (neurons). High levels of beta amyloid are associated with reduced levels of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. (Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers in the brain.) Acetylcholine is part of the cholinergic system, which is essential for memory and learning and is progressively destroyed in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Tangles. Neurofibrillary tangles are the damaged remains of macrotubules, the support structure that allows the flow of nutrients through the neurons. A key feature of these tangled fibers is an abnormal form of the tau protein, which in its normal version helps maintain healthy neurons.

- Loss of nerve cell connections. The tangles and plaques cause neurons to lose their connection to one another and die off. As the neurons die, brain tissue shrinks (atrophies).

Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

Although no treatment has been found for curing Alzheimer’s, scientists are making advances in better understanding the disease and how it progresses. In 2011, the U.S. National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association released updated criteria on defining and diagnosing Alzheimer’s. The new criteria place Alzheimer’s into three stages:

- Preclinical. In this stage, brain changes including amyloid buildup and nerve cell disruption are beginning to occur but symptoms are not yet evident. Researchers are studying various tests for biomarkers to better understand what these changes mean and what type of risk they may pose for progression to Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). MCI is marked by symptoms of memory problems but they are not severe enough to interfere with a person’s functioning or independence. People with MCI may or may not go on to develop Alzheimer’s dementia. Biomarker tests to better identify this stage are currently being developed.

- Alzheimer’s Dementia. This stage encompasses the spectrum of dementia severity from mild to severe. Symptoms are apparent and have gradually become worse over months or years. They are now significant enough to affect daily functional abilities. The most typical symptom is memory loss, particularly the learning and recall of recent information. Other symptoms may include difficulties in finding words, identifying and locating objects and faces, and problems with judgment and reasoning.

Causes

Scientists do not know what causes Alzheimer’s disease. It may be a combination of various genetic and environmental factors that trigger the process in which brain nerve cells are destroyed.

Genetic Factors

Genetics certainly plays a role in early-onset Alzheimer's, a rare form of the disease that usually runs in families. Scientists are also investigating genetic targets for late-onset Alzheimer's, which is the more common form. At this time, only one gene, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) has been definitively linked to late-onset Alzheimer's disease. However, only a small percentage of people carry the form of ApoE that increases the risk of late-onset Alzheimer's. Other genes or combinations of genes may be involved.

Environmental Factors

Researchers have investigated various environmental factors that may play a role in Alzheimer’s disease or that trigger the disease process in people who have a genetic susceptibility. Some studies have suggested an association between serious head injuries in early adulthood and Alzheimer’s development. Lower educational level, which may decrease mental and activity and neuron stimulation, has also been investigated. To date, there does not appear to be any evidence that infections, metals, or industrial toxins cause Alzheimer’s disease.

Risk Factors

Alzheimer's disease is the fifth leading cause of death in American adults age 65 and older. It affects more than 5 million Americans and millions more people worldwide.

Age

Age is the primary risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. The number of cases of Alzheimer's disease doubles every 5 years beyond age 65. According to the U.S. Alzheimer’s Association, 1 in 8 people age 65 and older have Alzheimer’s disease. About 6% of people age 65 to 74 have Alzheimer’s and nearly half (45%) of people age 85 years and older have the disease. While less common, Alzheimer’s can also affect younger people. About 200,000 Americans younger than age 65 have early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Gender

More women than men develop Alzheimer’s disease but this is most likely because women tend to live longer than men.

Race and Ethnicity

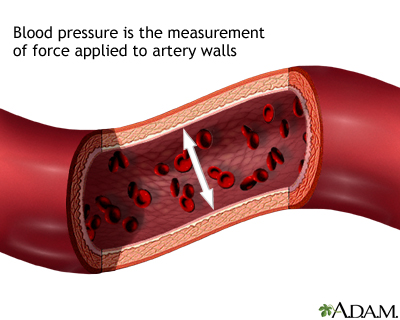

African Americans and Hispanics are at greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease than whites. This may be in part because they have a higher prevalence of medical conditions such as high blood pressure and diabetes, which are associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s.

Family History

People with a family history of Alzheimer's are at higher than average risk for the disease.

Heart and Vascular Diseases

Researchers are investigating whether diseases that affect the heart and vascular (blood vessel) system may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. These conditions include high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and type 2 diabetes. There is some evidence that controlling these conditions may help prevent Alzheimer’s disease.

Lifestyle Factors

Clinical trials have evaluated numerous substances for preventing Alzheimer’s disease but have not found any of them to be helpful. They included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), statin drugs, estrogen replacement therapy, folic acid supplementation, vitamin E, fish oil supplements, and herbal remedies such as ginkgo biloba.

However, certain lifestyle changes may help in Alzheimer’s disease prevention:

- Stay mentally active. Participating in intellectually engaging activity (such as doing crossword puzzles or learning a new language) may help reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease.

- Stay physically active. Exercise and regular physical activity of at least moderate intensity may help preserve cognitive function.

- Stay socially active. Personal relations and connections may help protect against Alzheimer’s disease.

- Eat a heart-healthy and brain-healthy diet. While no specific dietary factors have been found to prevent Alzheimer’s disease, a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet is healthy for the heart and the brain. Replace saturated fats and trans-fatty acids with unsaturated fats from plant and fish oils. Fish oil’s omega-3 fatty acids, which contain docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) are an excellent source of unsaturated fat. Eat lots of darkly colored fruits and vegetables, which are the best source for antioxidant vitamins and other nutrients. (Although there has been much research, there is little or no evidence that vitamin B or E supplements, or fish oil supplements, are protective. Food is the best source for these nutrients.) The Mediterranean Diet is an example of an eating plan that includes many of these recommendations.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Obesity leads to a more sedentary lifestyle and may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Obesity also increases the risk for heart and metabolic conditions that may be associated with Alzheimer’s disease development.

Symptoms

The early symptoms of Alzheimer's disease (AD) may be overlooked because they resemble signs of natural aging. However, extreme memory loss or other cognitive changes that disrupt normal life are not typical signs of aging. In addition, the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease do not begin abruptly; they develop gradually and worsen over the course of months or years.

Older adults who begin to notice a persistent mild memory loss of recent events may have a condition called mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI may be a sign of early-stage Alzheimer's in older people. Studies suggest that some, although not all, older individuals who experience such mild memory abnormalities can later develop Alzheimer's disease.

Patients may be aware of their symptoms or may be unaware that anything is wrong. The Alzheimer’s Association recommends that everyone learn these 10 warning signs of Alzheimer’s disease:

- Memory changes that disrupt daily life. Forgetfulness, particularly of recent events or information, or repeatedly asking for the same information

- Challenges in planning or solving problems. Loss of concentration (having trouble planning or completing familiar tasks, difficulty with abstract thinking such as simple arithmetic problems)

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks at home, at work, or at leisure

- Confusion about time or place. Difficulty recognizing familiar neighborhoods or remembering how you arrived at a location, confusion about months or seasons

- Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. Difficulty reading, figuring out distance, or determining color.

- Language problems. Forgetting the names of objects, mixing up words, difficulty completing sentences or following conversations

- Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps. Putting objects back in unusual places, losing things, accusing others of hiding or stealing.

- Impaired judgment and decision making. Dressing inappropriately or making poor financial decisions

- Withdrawal from work or social activities. No longer participating in familiar hobbies and interests.

- Mood and personality changes. Confusion, increased fear or suspicion, apathy and depression, anxiety. Signs can be loss of interest in activities, increased sleeping, sitting in front of the television for long periods of time.

Diagnosis

Alzheimer’s disease can only be definitely diagnosed after death when an autopsy of the brain is performed. However, Alzheimer's diagnosis is a very active area of research. The goal is to diagnose Alzheimer's while it is still in its early stages. Researchers are making progress studying biomarkers, brain imaging, and other new techniques.

At this time, there is no one test that confirms a diagnosis of Alzheimer's. Doctors use a variety of tests to make a probable diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Medical History and Physical Examination

The doctor will ask questions about the patient’s health history, including other medical conditions the patient has, recent or past illnesses, and progressive changes in mental function, behavior, or daily activities. The doctor will ask about use of prescription drugs (it is helpful to bring a complete list of the patient’s medications) and lifestyle factors, including diet and use of alcohol. The doctor will evaluate the patient’s hearing and vision, and check blood pressure and other physical signs. A neurological test will also be conducted to check reflexes, coordination, and eye movement.

Laboratory Tests

Blood and urine samples may be collected. They can help the doctor evaluate other possible causes of dementia, such as thyroid imbalances or vitamin deficiencies. Researchers are studying measuring levels of amyloid beta and tau proteins in spinal fluid samples to help identify patients with memory problems who may be at risk for developing Alzheimer’s.

Neuropsychological Tests

Several psychological tests are used to assess difficulties in attention, perception, memory, language, problem-solving, social, and language skills. These tests can also be used to evaluate mood problems such as depression.

One commonly used test is the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), which uses a series of questions and tasks to evaluate cognitive function. For example, the patient is given a series of words and asked to recall and repeat them a few minutes later. In the clock-drawing test, the patient is given a piece of paper with a circle on it and is asked to write the numbers in the face of a clock and then to show a specific time on the clock.

Brain-Imaging Scans

Imaging tests are useful for ruling out blood clots, tumors, or other structural abnormalities in the brain that may be causing signs of dementia. These tests include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or positron-emission testing (PET) scans.

Researchers are using MRIs and PET scans to study new approaches to diagnosing Alzheimer’s in earlier stages of the disease. Methods include measuring the volume and shrinkage (atrophy) of brain tissue with MRI and evaluating the brain’s use of glucose with PET. In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved florbetapir (Amyvid), a radioactive dye that is used with PET scans to evaluate beta amyloid density.

Ruling out Other Causes of Memory Loss or Dementia

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia. However, other causes of dementia in the elderly can include:

- Vascular dementia (abnormalities in the vessels that carry blood to the brain)

- Lewy bodies variant (LBV), also called dementia with Lewy bodies

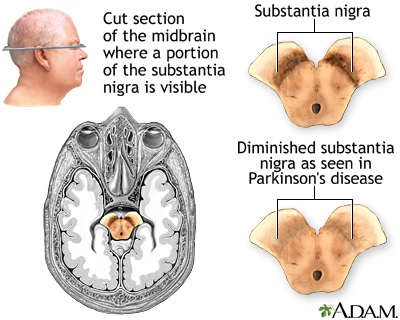

- Parkinson's disease

- Frontotemporal dementia

Vascular Dementia. Vascular dementia is primarily caused by either multi-infarct dementia (multiple small strokes) or Binswanger's disease (which affects tiny arteries in the midbrain).

Lewy Bodies Variant. Lewy bodies are abnormalities found in the brains of patients with both Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's. They can also be present in the absence of either disease; in such cases, the condition is called Lewy bodies variant (LBV). In all cases, the presence of Lewy bodies is highly associated with dementia.

Parkinson's Disease. Some of the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s can be similar and the diseases may coexist. However, unlike Alzheimer's, language is not usually affected in Parkinson's related dementia.

Frontotemporal Dementia. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a term used to describe several different disorders that affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Although some of the symptoms can overlap with Alzheimer’s, people who develop this condition tend to be younger than most patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Other Conditions. A number of conditions, including many medications, can produce symptoms similar to Alzheimer's. These conditions include severe depression, drug abuse, thyroid disease, vitamin deficiencies, blood clots, infections, brain tumors, and various neurological or vascular disorders.

Treatment

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease or treatment to stop its progression or reverse the symptoms. Most drugs used to treat Alzheimer's are aimed at slowing the rate at which symptoms become worse. The benefit from these drugs is generally small, and patients and their families may not even notice any benefit.

Stages

Alzheimer’s disease is classified into various stages that range from mild to moderate to severe. In the final stages of Alzheimer’s, the patient is unable to communicate and is completely dependent on others for care.

The lifespan of patients with Alzheimer's is generally reduced, although a patient may live anywhere from 3 - 20 years after diagnosis. The final phase of the disease may last from a few months to several years, during which time the patient becomes increasingly immobile and dysfunctional.

Home Treatment in Early Stages

Telling the Patient. Often doctors will not tell patients that they have Alzheimer's. If a patient expresses a need to know the truth, it should be disclosed. Both the caregiver and the patient can then begin to address issues that can be controlled, such as access to support groups and drug research.

Mood and Emotional Behavior. Patients display abrupt mood swings, and many become aggressive and angry. Some of this erratic behavior is caused by chemical changes in the brain. But it may also be due to the experience of losing knowledge and understanding of one's surroundings, causing fear and frustration that patients can no longer express verbally.

The following recommendations for caregivers may help soothe patients and avoid agitation:

- Keep environmental distractions and noise (television, radio) at a minimum if possible. (Even normal noises, such as people talking outside a room, may seem threatening and trigger agitation or aggression.)

- Speak clearly in a gentle tone of voice using simple words and short sentences. Allow enough time for a response.

- Offer diversions, such as a snack or car ride, if the patient starts shouting or exhibiting other disruptive behavior.

- Maintain as natural an attitude as possible. Patients with Alzheimer's disease can be highly sensitive to the caregiver's underlying emotions and react negatively to patronization or signals of anger and frustration.

- Showing movies or videos of family members and events from the patient's past may be comforting.

Although much attention is given to the negative emotions of patients with Alzheimer's disease, some patients become extremely gentle, retaining an ability to laugh at themselves or appreciate simple visual jokes even after their verbal abilities have disappeared. Some patients may seem to be in a drug-like or "mystical" state, focusing on the present experience as their past and future slip away. Encouraging and even enjoying such states may bring some comfort to a caregiver.

There is no single Alzheimer's personality, just as there is no single human personality. All patients must be treated as the individuals they continue to be, even after their social self has vanished.

Bathing and Dressing. For the caregiver, grooming the patient can be challenging. For one thing, many patients resist bathing or taking a shower. Some patients find bathing confusing or frightening. Some spouses find that showering with their afflicted mate can solve the problem for a while. Establishing a daily and familiar routine can be helpful.

Often patients with Alzheimer's disease lose their sense of color and design and will put on odd or mismatched clothing. It is important to maintain a sense of humor and perspective and to learn which battles are worth fighting and which ones are best abandoned. Caregivers can pick a selection of outfits and allow the patient to select a favorite. Try to choose clothes that are easy to put on and take off.

Driving. Patients at any stage of dementia -- including mild -- are at high risk for unsafe driving. Typical Alzheimer’s symptoms -- such as difficulty remembering and navigating locations, poor judgment, and slow decision making -- all pose dangers for driving. A history of recent citations, crashes, or aggressive or reckless driving are specific warning signs. As soon as Alzheimer's is diagnosed, the patient should be prevented from driving.

Wandering. A potentially dangerous trait is the patient's tendency to wander. At the point the patient develops this tendency, many caregivers feel it is time to seek out nursing homes or other protective institutions for their loved ones. For those who remain at home, the following precautions are recommended:

- Locks should be installed outside the door, which the caregiver can open, but the patient cannot.

- Alarms may be installed at exits.

- A daily exercise program should be implemented, which may help tire the patient.

- The caregiver should contact organizations, such as Alzheimer's Association or Medic Alert, for identification supplies and procedures that help locate patients who wander away from home and become lost.

Speech Problems. Speech therapy combined with Alzheimer's disease medications may be helpful for maintaining verbal skills in patients with mild symptoms.

Sexuality. In many cases, the patient becomes uninhibited sexually. At the same time, the patient's physical deterioration and receding capacity to recognize the spouse as a known and loved individual can make sexual activity unattractive for the caregiving spouse. Other patients may lose interest in sex. If sexual issues are a problem, they should be discussed openly with the doctor. Ways should be found to maintain non-sexual physical affection that can bring comfort to both the patient and the spouse.

Home Treatment During Later Stages

Patients with Alzheimer's disease need 24-hour a day attention. Even if the caregiver has the resources to keep the patient at home during later stages of the disease, outside help is still essential. If available, home visits by a health profession can have a favorable impact on survival and delay the need for a nursing home.

Incontinence. Incontinence (loss of control of bowel or urine function) is a primary reason why many caregivers decide to seek nursing home placement. When the patient first shows signs of incontinence, the doctor should make sure that it is not caused by an infection. Urinary incontinence may be controlled for some time by trying to monitor times of liquid intake, feeding, and urinating. Once a schedule has been established, the caregiver may be able to anticipate incontinent episodes and get the patient to the toilet before they occur.

Immobility and Pain. As the disease progresses, patients become immobile, literally forgetting how to move. Eventually, they become almost entirely wheelchair-bound or bedridden. Bedsores can be a major problem. Sheets must be kept clean, dry, and free of food. The patient's skin should be washed frequently, gently blotted thoroughly dry, and moisturizers applied. The patient should be moved every 2 hours and the feet kept raised with pillows or pads. Exercises should be administered to the legs and arms to keep them flexible.

Dehydration. Dehydration can become a problem. It is important to encourage fluid intake equal to 8 glasses of water daily. Coffee and tea are mild diuretics that may deplete fluid.

Eating Problems. Weight loss and the gradual inability to swallow are two major related problems in late-stage Alzheimer's and are associated with an increased risk of death. Weight gain, however, is linked to a lower risk of dying. The patient can be fed through a feeding syringe, or the caregiver can encourage chewing action by pushing gently on the bottom of the patient's chin and on the lips. The caregiver should offer the patient foods of different consistency and flavor. Because choking is a danger, the caregiver should learn to administer the Heimlich maneuver. In very late stages, some caregivers choose feeding tubes for the patient. They should be aware that feeding tubes have no measurable impact on survival.

Care for the Caregiver

About 80% of patients with Alzheimer's disease are cared for at home by family members, who often lack adequate support, finances, or training for this difficult job. Few diseases disrupt patients and their families so completely or for so long a period of time as Alzheimer's. The patient's family endures two separate losses and grieves twice:

- First, they must grieve for the ongoing disappearance of the personality they recognize.

- Finally, the caregiver must grieve the actual death of the person.

Often, caregivers themselves begin to show signs of psychological stress or ill health. Depression, empathy, exhaustion, guilt, and anger can play havoc with even a healthy individual faced with the care of a loved one suffering from Alzheimer's.

Support services can greatly improve caretakers’ quality of life and make it easier for them to continue caring for patients in their homes. Such support includes individual and family counseling, telephone counseling, support groups, and stress management and problem-solving techniques. Such help may help relieve depression and improve self-confidence in caregivers, and possibly enable the patient to remain in the home.

Nursing Homes and Other Outside Services

A point comes when the most devoted caregiver may need to consider institutionalizing the patient. That point is determined not only by the caregiver's emotional endurance, but also by their physical strength and stamina, as a patient typically takes on the random, undisciplined behavior of a very young child. Financial considerations in finding a nursing home are often paramount, but the kind of care is equally important. Although fully half of all nursing home patients suffer from Alzheimer's, not all nursing homes have programs specifically designed for them. Some institutions may claim that they do, but often they simply group patients together without offering any special programs. If a caregiver manages to find a facility that offers good services, it may be located far from home, making visits difficult. The caregiver must then decide whether superior care at a distant institution is worth seeing the patient less frequently. When the patient's illness becomes terminal, a hospice program may be another option.

Twelve Steps for Caregivers

1. Although I cannot control the disease process, I need to remember I can control many aspects of how it affects my relative.

2. I need to take care of myself so that I can continue doing the things that are most important.

3. I need to simplify my lifestyle so that my time and energy are available for things that are really important at this time.

4. I need to cultivate the gift of allowing others to help me, because caring for my relative is too big a job to be done by one person.

5. I need to take one day at a time rather than worry about what may or may not happen in the future.

6. I need to structure my day because a consistent schedule makes life easier for me and my relative.

7. I need to have a sense of humor because laughter helps to put things in a more positive perspective.

8. I need to remember that my relative is not being difficult on purpose; rather their behavior and emotions are distorted by the illness.

9. I need to focus on and enjoy what my relative can still do rather than constantly lament over what is gone.

10. I need to increasingly depend upon other relationships for love and support.

11. I need to frequently remind myself that I am doing the best that I can at this very moment.

12. I need to draw upon the Higher Power, which I believe is available to me.

Source: The American Journal of Alzheimer's Care and Related Disorders & Research, Nov/Dec 1989

Medications

Most drugs used to treat Alzheimer's, and those under investigation, are aimed at slowing progression. There are no cures to date. In addition, the improvements from some of these drugs may be so modest that patients and their families may not notice benefit.

The FDA has approved two drug classes to treat the cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease:

- Cholinesterase inhibitors (generally used to treat mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's; donepezil is also approved for treatment of severe dementia)

- N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists (used to treat moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's)

All of the drugs approved for treatment of Alzheimer's disease are expensive. While there are generally no serious risks associated with these medications, these drugs can have a number of bothersome side effects, including indigestion, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, muscle cramps, and fatigue.

Patients and caregivers should ask their doctors the following questions about when and if to use these drugs:

- Will there be a noticeable change in behavior or function of the patient? The published studies that enabled approval of these drugs for treatment of Alzheimer's disease demonstrated modest benefit when evaluating patients using cognitive and functional scales. While these scales are important for consistency of recording and performing studies, the benefit demonstrated in clinical trials does not necessarily translate into any significant change in how patients function in their daily lives. There is, in fact, no evidence that use of these medications extends the time before a patient requires care in an institutional setting, such as a nursing home.

- Is it better to use these drugs early in the course of Alzheimer's disease? Treating patients with mild cognitive impairment (persistent mild memory loss of recent events but no diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease) does not seem to prevent patients from developing Alzheimer's disease.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors (Donepezil, Rivastigmine, Galantamine)

Cholinesterase inhibitors are designed to protect the cholinergic system, which is essential for memory and learning and is progressively destroyed in Alzheimer's. These drugs work by preventing the breakdown of the brain chemical acetylcholine. The first cholinesterase inhibitor, tacrine (Cognex), was approved in 1993 but is rarely prescribed today due to safety concerns of liver damage.

The three most commonly prescribed cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease are donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine:

- Donepezil. Donepezil (Aricept, generic) is the only Alzheimer's drug approved for all stages of dementia, from mild to severe. It is taken once a day and has only modest benefits at best.

- Rivastigmine. Rivastigmine (Exelon) targets two enzymes: Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase. It is available in pill form and also available as a skin patch. It is approved for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease.

- Galantamine. Galantamine (Razadyne, generic) protects the cholinergic system and stimulates nicotine receptors to produce more acetylcholinesterase. It is approved to treat mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease.

Side Effects. Common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors, especially when taken at higher doses, may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and upset stomach. Rivastigmine and galantamine tend to have more side effects than donepezil, and may also cause weight loss and loss of appetite. Cholinesterase inhibitors may increase the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding or ulcers, especially when used with NSAIDs (which can also cause gastric irritation).

Some drugs known as anticholinergics may offset the effects of the Alzheimer's disease pro-cholinergic drugs. Such drugs include antihistamines, antipsychotic drugs, and some antidepressants and anti-incontinence drugs.

Effectiveness. Comparative studies have reported little differences in effectiveness among these drugs. In any case, the benefits of these drugs are far from dramatic and may often not be noticeable in everyday life. In fact, many doctors have reservations about developing any additional drugs that affect the cholinergic system since, at best, they only slow progression and do not appear to affect the basic destructive disease process. When patients go off the drugs, the deterioration continues.

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NDMA) Receptor Antagonist (Memantine)

Memantine (Namenda) is approved for treatment of moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. (It does not appear to be effective for mild Alzheimer’s disease. Most cholinesterase inhibitors are used to treat mild-to-moderate stages of the disease.) By blocking NDMA receptors, memantine protects against the overstimulation of glutamate, an amino acid that excites nerves and, in excess, is a powerful nerve-cell killer.

Memantine is prescribed either alone or in combination with donepezil. Studies indicate that memantine may help modestly improve cognitive function and delay the progression of Alzheimer’s disease for up to 1 year. Side effects are generally mild but may include dizziness, drowsiness, or fainting.

Treating Symptoms Associated with Alzheimer's

Depression. Antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), including fluoxetine (Prozac, generic) and sertraline (Zoloft, generic), may help reduce depression, irritability, and restlessness associated with Alzheimer's in some patients.

Apathy. Depression is often confused with apathy. An apathetic patient lacks emotions, motivation, interest, and enthusiasm while a depressed patient is generally very sad, tearful, and hopeless. Apathy may respond to stimulants, such as methylphenidate (Ritalin, generic), rather than antidepressants.

Psychosis. Antipsychotic drugs are used to treat verbally or physically aggressive behavior and hallucinations. Because older antipsychotic drugs, such as haloperidol (Haldol, generic), have severe side effects, most doctors now prescribe newer atypical antipsychotics, such as risperidone (Risperdal, generic) or olanzapine (Zyprexa).

However, these newer antipsychotic drugs can cause serious side effects, including confusion, sleepiness, and Parkinsonian-like symptoms. In addition, studies indicate that their safety risks may outweigh any possible benefits. Studies show that both atypical and older antipsychotics produce a slightly increased rate of death in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia and that atypical antipsychotics work no better than placebo in controlling psychosis, aggression, and agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s.

Most doctors recommend delaying prescribing antipsychotic medication unless absolutely necessary. They recommend first trying behavioral treatments and controlling changes in the patient’s environment and routine. Anti-seizure drugs, such as carbamazepine (Tegretol, generic) or valproate (Depakote, generic), can also sometimes treat agitation and other psychotic symptoms.

Disturbed Sleep. Patients with Alzheimer's disease commonly experience disturbances in their sleep/wake cycles. Moderately short-acting sleeping drugs, such as temazepam (Restoril, generic), zolpidem (Ambien, generic), or zaleplon (Sonata, generic), or sedating antidepressants, such as trazodone (Desyrel, generic), may be useful in managing insomnia. However, these drugs increase the risk of falling, confusion, and abnormal behavior and must be used with considerable caution and restraint.

Some research suggests that exposure to brighter-than-normal artificial light during the day for patients with normal vision may help reset wake/sleep cycles and prevent nighttime wandering and sleeplessness. Sleep hygiene methods (regular times for meal and bed, exercise, avoiding caffeine) may also be helpful.

Resources

- www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers -- Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center (U.S. National Institute on Aging)

- www.alz.org -- Alzheimer's Association

- www.alzfdn.org -- Alzheimer's Foundation of America

- www.alz.co.uk -- Alzheimer's Disease International

- www.aan.com -- American Academy of Neurology

- www.medicalert.org -- Medic Alert

- www.clinicaltrials.gov -- Find clinical trials

- www.medicare.gov/NHCompare/Home.asp -- Find a nursing home

References

ADAPT Research Group, Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC, Green RC, Martin BK, Meinert C, et al. Naproxen and celecoxib do not prevent AD in early results from a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007 May 22;68(21):1800-8. Epub 2007 Apr 25.

Albert MS, Dekosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011 May;7(3):270-9. Epub 2011 Apr 21.

Alzheimer's Association. 2012 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's Dement. 2012 Mar;8(2):131-68.

Au R, Green RC, Farrer LA, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of developing Alzheimer disease: results from the Framingham Study. Arch Neurol. 2006 Nov;63(11):1551-5.

Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, Arean PA. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Nov 13;166(20):2182-8.

Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A, Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2011 Mar 19;377(9770):1019-31. Epub 2011 Mar 1.

Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 11. [Epub ahead of print]

Birks J, Grimley Evans J. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21;(1):CD003120.

Daviglus ML, Bell CC, Berrettini W, Bowen PE, Connolly ES Jr, Cox NJ, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference statement: preventing alzheimer disease and cognitive decline. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Aug 3;153(3):176-81. Epub 2010 Jun 14.

De Meyer G, Shapiro F, Vanderstichele H, Vanmechelen E, Engelborghs S, De Deyn PP, et al. Diagnosis-independent Alzheimer disease biomarker signature in cognitively normal elderly people. Arch Neurol. 2010 Aug;67(8):949-56.

Durga J, van Boxtel MP, Schouten EG, Kok FJ, Jolles J, Katan MB, et al. Effect of 3-year folic acid supplementation on cognitive function in older adults in the FACIT trial: a randomised, double blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2007 Jan 20;369(9557):208-16.

Gu Y, Nieves JW, Stern Y, Luchsinger JA, Scarmeas N. Food combination and Alzheimer disease risk: a protective diet. Arch Neurol. 2010 Jun;67(6):699-706. Epub 2010 Apr 12.

Isaac MG, Quinn R, Tabet N. Vitamin E for Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jul 16;(3):CD002854.

Iverson DJ, Gronseth GS, Reger MA, Classen S, Dubinsky RM, Rizzo M; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter update: evaluation and management of driving risk in dementia: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010 Apr 20;74(16):1316-24. Epub 2010 Apr 12.

Jack CR Jr, Albert MS, Knopman DS, McKhann GM, Sperling RA, Carrillo MC, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011 May;7(3):257-62. Epub 2011 Apr 21.

Knopfman DS. Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil Medicine. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:chap 425.

Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, Foster JK, van Bockxmeer FM, Xiao J, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008 Sep 3;300(9):1027-37.

Mayeux R. Early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 10;362(4):2194-2201.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011 May;7(3):263-9. Epub 2011 Apr 21.

Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jan 28;362(4):329-44.

Quinn JF, Raman R, Thomas RG, Yurko-Mauro K, Nelson EB, Van Dyck C, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010 Nov 3;304(17):1903-11.

Regan C, Katona C, Walker Z, Hooper J, Donovan J, Livingston G. Relationship of vascular risk to the progression of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006 Oct 24;67(8):1357-62.

Scarmeas N, Luchsinger JA, Schupf N, Brickman AM, Cosentino S, Tang MX, et al. Physical activity, diet, and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2009 Aug 12;302(6):627-37.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Higgins JP, McShane R. Lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011 Apr 11. [Epub ahead of print]

Seshadri S, Fitzpatrick AL, Ikram MA, DeStefano AL, Gudnason V, Boada M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2010 May 12;303(18):1832-40.

Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008 Sep 11;337:a1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1344.

Snitz BE, O'Meara ES, Carlson MC, Arnold AM, Ives DG, Rapp SR, et al. Ginkgo biloba for preventing cognitive decline in older adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009 Dec 23;302(24):2663-70.

Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011 May;7(3):280-92. Epub 2011 Apr 21.

Yang L, Rieves D, Ganley C. Brain amyloid imaging--FDA approval of florbetapir F18 injection. N Engl J Med. 2012 Sep 6;367(10):885-7.

|

Review Date:

9/26/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |